IRISH PARIS

Revolutionaries

From the time of the French Revolution until independence and beyond, Paris was a major focal point for Irish rebels. Arthur O’Connor, born in Mitchelstown, knew France well before he and Lord Edward Fitzgerald met General Lazare Hoche in 1796 with a view to organising an invasion of Ireland.

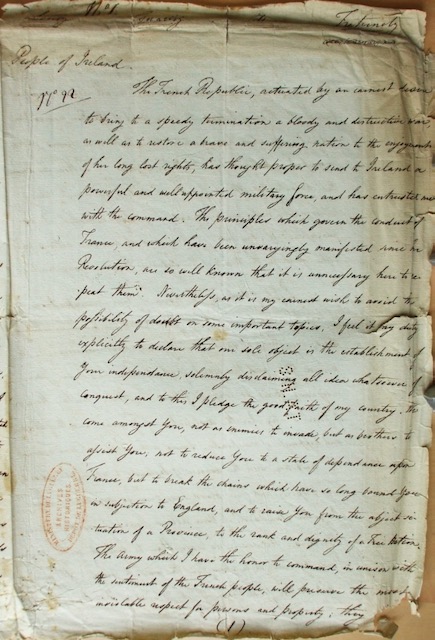

But it was Theobald Wolfe Tone who embarked on Hoche’s hapless expedition to Bantry Bay in December 1796. Wolfe Tone had arrived in Paris incognito in February of that year. After the failure at Bantry Bay, Wolfe Tone went back to Paris and campaigned with the French in the Army of the Rhine and in Holland before embarking in Brest on the ship that would bring him to Lough Swilly, and his death, in November 1798. But his family stayed on in Paris until 1816, with his son, William, winning the Légion d’Honneur for bravery fighting in Napoleon’s army.

As for O’Connor, he turned up again in Paris in 1802 along with Thomas Emmet, when the two United Irishmen vied for French attention. There was little love lost between O’Connor and Emmet, who seems to have lost the contest. Thomas’s brother Robert had already come to Paris in early 1801 and together with other exiled United Irishmen tried to gain French support for another rebellion in Ireland. Alas, the Peace of Amiens intervened, ending hostilities between France the Britain for 14 months. While Robert left Paris in the summer of 1802 to organise his unsuccessful rebellion, Thomas Emmet stayed in Paris until 1804 when, disillusioned by the course of events (including the execution of Robert), he left for the U.S, where he had a successful legal career.

In 1804, O’Connor was appointed major general in the Irish Legion, part of another wistful plan to invade Ireland. He expressed his support for Napoleon when the latter escaped from the island of Elba in 1815 and seized power in Paris. For this, O’Connor was served an expulsion order by King Louis XVIII but managed to stay in France after pulling a few strings. Later he became major of Le Bignon-Mirabeau, the village south of Paris where he lived.

In the middle of the century, the lynchpin of Irish nationalism in Paris was undoubtedly John Patrick Leonard (born in Cork in 1814), who lived in the city from 1834 until his death 55 years later. Leonard hosted the leading Young Irelanders when they arrived in Paris in 1848 and was involved in organising all kinds of nationalist initiatives designed to draw Ireland to the attention of the French authorities thereafter. Among the Fenian luminaries that Leonard helped or met during their Paris sojourns were John Devoy, John Mitchel, John O’Leary and James Stephens. The latter spent many miserable years in Paris, for he was frequently penniless, reducing him to scrounging board and lodgings from fellow Irish exiles. Having been briefly expelled from France to Belgium for his revolutionary activities, Stephens finally made it back to Dublin in 1891. The far better-integrated Patrick Leonard was at the centre of the Anciens Irlandais group that organised a St. Patrick’s Day dinner each year in Paris and in 1869 he backed a scheme to help France populate Algeria with Irish peasants. After much trying, Leonard finally obtained the Légion d’Honneur in 1871 for his work with the Irish Ambulance during the Franco-Prussian war.

Other Paris-based revolutionaries included Eugene Davis (born in Clonakilty in 1857) and the four Casey Brothers. Together with Patrick Egan, James Stephens, John O’Leary and John O’Connor, they formed the nucleus of the Fenians’ outpost in Paris for a short period in the years after the failed 1867 rebellion. The Casey brothers served in the French forces during the Franco-Prussian War. One of the brothers, Andrew, was decorated for bravery, while another, Joseph, appears as Kevin Egan in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Davis became acting editor for the United Ireland newspaper in Paris when it was banned in the UK. Having attracted the interest of British intelligence, Davis was expelled from France along with James Stephens in 1885.

The revolutionary baton was taken up at the end of the 19th century by Maud Gonne. Starting out in Paris as an actress, the English-born Gonne founded the Association irlandaise and the Irlande Libre newspaper. In 1903, she married Major John MacBride, who had fought with the Boers against the British in the Boer War. From their brief marriage was born Seán MacBride in 1904, with the event signalled in the Dublin newspapers as “the arrival of the latest Irish rebel”. Maud Gonne left France in 1917, but Seán, who spent his childhood in the city, was sent to Paris in 1920 on a mission to obtain arms for the IRA and worked there for a while as a journalist during the 1920s.

Paris also had a role in the Troubles. Three members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) made the headlines in 1982 when their apartment in the Paris suburb of Vincennes was raided following a wave of bomb attacks on Jewish interests in the city. The Irish had nothing to do with these attacks, but the French police needed some positive publicity, and so guns and explosives were conveniently planted in the apartment of the three INLA members. This led to a series of high-profile court cases, with the ‘Irlandais de Vincennes’ rewarded a symbolic one franc in return for wrongful arrest. Less than three years later, Seamus Ruddy from Newry, an English teacher in Paris, was killed in an internal INLA dispute in 1985. After digs in various forests, his remains were finally found in a forest near Rouen in May 2017.