IRISH PARIS

Soldiers and Politicians

The defeat of the Irish chieftains at Kinsale in December 1601 unleashed many destitute Irish soldiers and their families on continental Europe, many arriving in Paris. A plague of Irish beggars in the city led to a repatriation drive, with 500 of them packed off back to Ireland on a single boat in 1606. At the end of the same century, in 1691, the Treaty of Limerick set off another wave of emigration so that the French army was able to recruit thousands of Irishmen and field several Irish regiments during the 18th century. An ‘Irish Brigade’ under Charles O’Brien distinguished itself in particular at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745. And Irish veterans were among the first residents of the Invalides, opened in 1765 as a home for old and infirm soldiers, leaving their trace in the establishment’s registry.

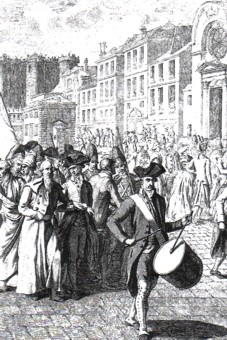

The storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789 also had its Irish protagonists. One of only seven prisoners inside the prison that day was a Dubliner called F.X. Whyte, who had served in Lally’s regiment in the Irish Brigade. One of the titular chaplains of the Bastille at the time was one Thomas MacMahon from Eyrecourt in Co. Galway. And one of the ring-leaders of the Parisian mob that stormed the Bastille that day was a boot-maker of Clare descent called Joseph Kavanagh. His central role in the procedures was the theme of a pamphlet that came out shortly afterwards entitled Les exploits glorieux du célèbre Cavanagh, cause première de la liberté française. Other Irishmen involved in the storming of the Bastille included James Bartholomew Blackwell, also from Clare, and Count Robert O’Shee from Tipperary.

But revolution, “like Saturn, devours its own children”. Parisian Irish who fell victim to the Revolution included James O’Moran, a general in the army of the North, who was guillotined on Place de la Concorde in March 1794 during the period called ‘the Terror’. Another general of Irish origin, Arthur Dillon, suffered the same fate a month later. Like Dillon, Dubliner Thomas Ward and his servant, Limerick-born John Malone, were arrested for ‘intelligence with the enemy’. They were both executed on 23 July, 1794, as was a priest called Pierre O’Brennan.

Other Irishmen fared better in the revolutionary armies. Charles Jennings Kilmaine, whose name can be seen inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe, fought for the French monarchy in Africa and the American War of Independence, before fighting for the new revolutionary regime. Kilmaine and his wife were briefly thrown in prison during the Terror, but he bounced back and distinguished himself in supressing a working-class revolt in eastern Paris in May 1795.

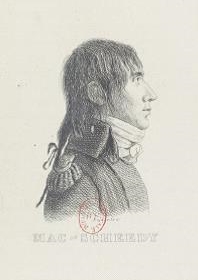

William Lawless and Bernard MacSheehy were both United Irishmen who wound up as officers in the ill-stared Irish Legion, created by Napoleon with a view to invading Ireland. Once invasion plans were abandoned, officers like Lawless fought in the Napoleonic armies elsewhere in Europe. MacSheehy, who rose to become effective head of the Irish Legion before being forced out, was killed in the Battle of Eylau in East Prussia in 1807, while his cousin, Patrice Maurice MacSheehy, was killed in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

William Corbet (born in Co. Cork in 1779) and Miles Byrne (born in Monaseed, Co. Wexford in 1780) met cannily similar destinies. Both were involved in the United Irishmen, both joined the ephemeral Irish Legion in France, and both as far away as Greece for the restored French monarchy. Cherry on the cake, they were both buried in Montmartre cemetery, although only Byrne’s tomb remains. The university-educated Corbet rose higher in the army hierarchy than Byrne, and had two brothers who also fought for France. But unlike Corbet, Byrne lived long enough to become reportedly the only survivor of the 1798 rebellion to have his photo taken and he left a wonderful memoir.

Later in the century, a rather louche Irishman appeared in the Paris firmament. James Dyer MacAdaras (born in Rathmines in 1838) first drew the attention of the French authorities when he offered to raise an Irish brigade to fight alongside them in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). MacAdaras’s involvement in the half-baked scheme remains murky, but he came out of the war calling himself a ‘general’. After a period in the US, he was back in Paris in 1887, when he managed to have himself elected as a member of parliament.

Cosmopolitan, French-speaking Irishmen were present in force to press the case for Irish independence in the years following World War One. In 1920, Michael MacWhite (born in Co. Cork in 1889) managed to pull off a stunt when he hijacked a public commemoration of Admiral Hoche in Versailles to lay a wreath on behalf of the Irish republic. George Gavan Duffy tried to persuade the US president to visit Ireland, but only managed to have himself expelled from France. Others worked during the Versailles peace treaty to produce propaganda material such as the Bulletin irlandais, but with mixed success. It was only in 1930 that the first permanent abode was found for the Irish Legation in Paris, at 37 bis rue de Villejust in the 16th arrondissement (now home of the Congolese embassy).

It would be remiss of a brief survey of Irish politicians in Paris to forget the deeds of some more recent politicos. Charles Haughey was a regular visitor to Paris, often in the company of his mistress, Terry Keane. He paid visits to Charvet on the Place Vendôme to buy tailor-fitted suits and shirts and was invited to the palatial home of the Lebanese businessman and horse breeder Mahmoud Fustuq in Chantilly (“the most spectacular momument to vulgarity imaginable,” according to Keane). Then there was Haughey’s acolyte, Bertie Aherne, who travelled to the village of Gallardon south of Paris in August 2003 for the marriage of his daughter, Georgina, to Nicky Byrne of Westlife fame. Hello! magazine paid the happy couple £850,000 for exclusive photo rights to the event. Ah! The blissful years of the Celtic Tiger.